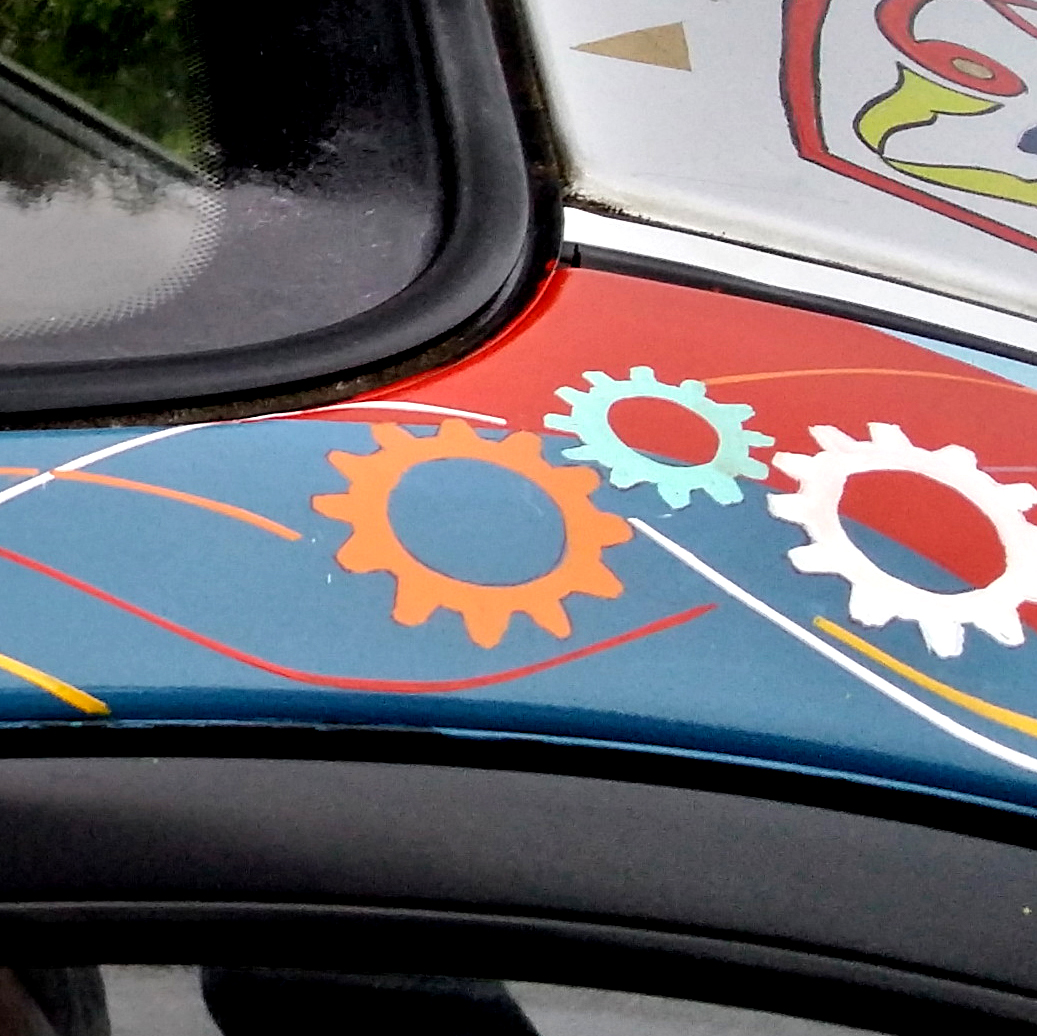

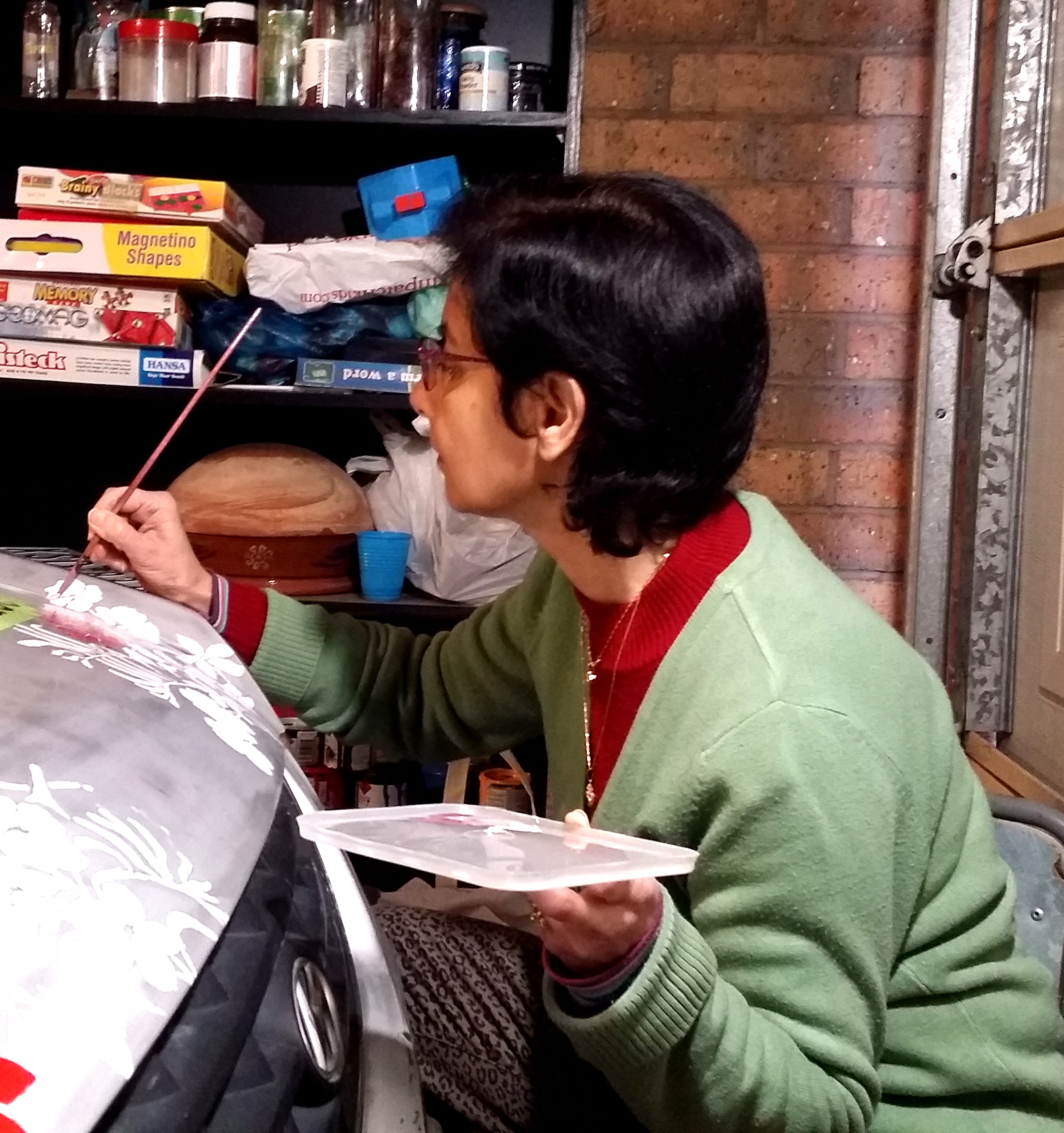

The car donated for the project was a mid-sized sedan, a 2004 Hyundi Accent. Though not a gem of a design from a modern prospective, the car had a clean, ‘healthy’ surface, with a minor ‘dimple’ on the left side but nothing major that could not be fixed with some muscle power. I started doodling the designs on the sketch pad but soon realized that to get a true appreciation of the area involved I needed to work on actual scale. I scaled off the sizes from the free vector images available on the net to rolls of paper and soon had a paper equivalent of the car surface.

It was only then; that the sheer scale of what I was trying to achieve truly dawned on me. Compared to a typical size painting, the available surface area on the car is enough for one or two very large size murals or easily 10-20 pieces of artwork!

This was further complicated by the fact that unlike paper the external surface of the car is not uniform. Each car has a unique identity and persona; and the car body stylist and designers spend a huge amount of effort to get the contours and the shapes just right. Working on 1: 1 scale drawing provided me an opportunity to tap into these forms and lines to highlight various aspects of the composition.

CONGRATULATION IT'S........A CAR !

Just as naming a child is an exciting time and an important first step in shaping their identity, naming one’s ride has a nostalgic appeal, especially for oldies like me. In my younger years; owning a car was considered a step towards self-reliance and freedom. As the intent was to use the SalamMobile as a mascot for the festival, SalamFest team thought it would be nice to give the car a nick-name of sort.

As the car was inspired by truck art, the initial tendency was to pick names from Urdu and other regional languages. We wanted to select a single syllable word which would be easier to palate for the western tongue. I was tempted to name the car Harry (after the first camel which landed in Australia in 1840), but reverted against it when I realize that Harry the camel had a reputation for being ill-tempered. I even contemplated ‘Paulie’ after the animation parrot character which spoke and narrated its journey to its owner but refrained myself from suggesting this name due to possible association of the name with one of the stalwarts of ultra-right wing politics in this country who has the tendency to capture headlines for all the wrong reasons.

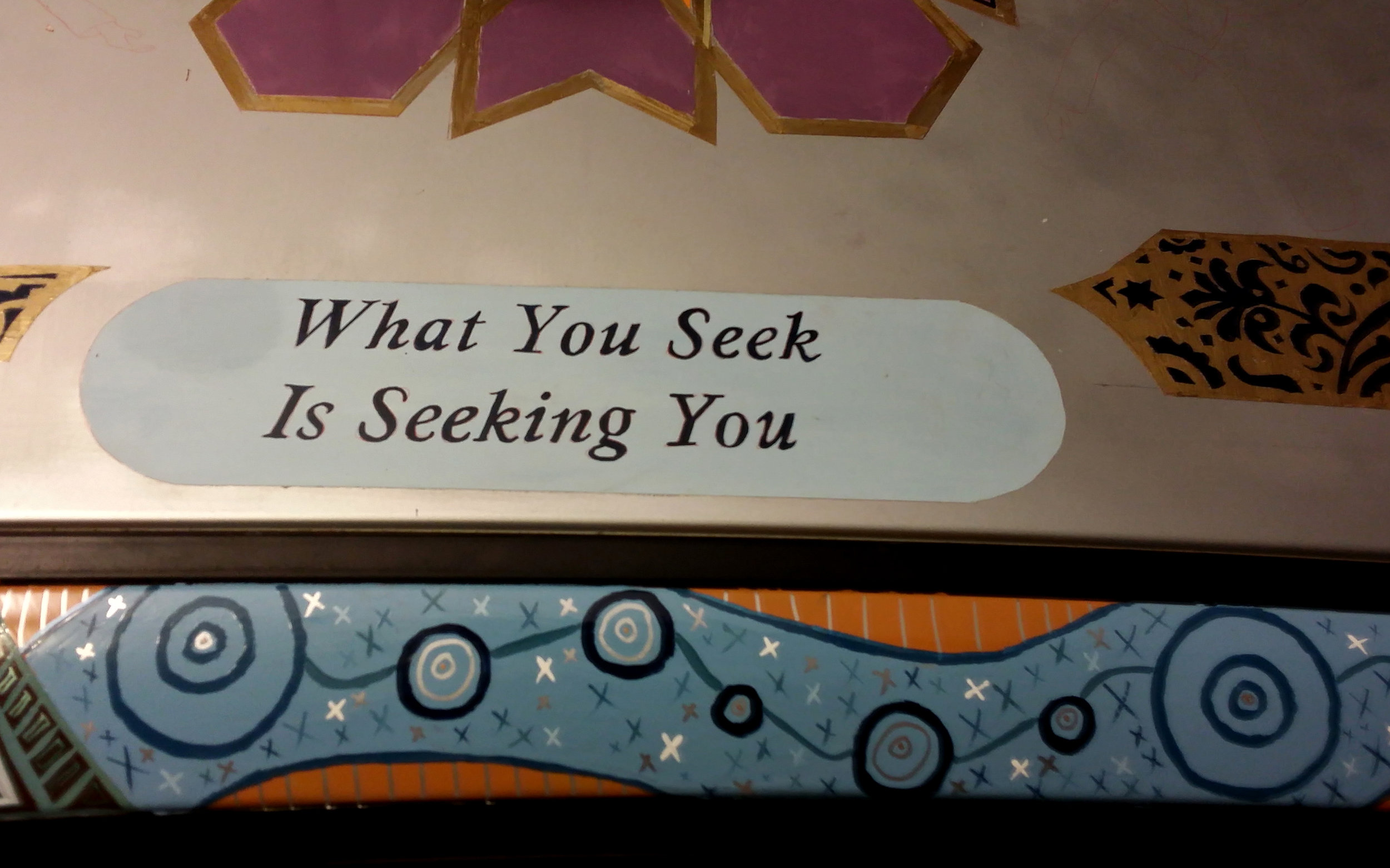

Love, peace and compassion are the cornerstones of Salamfest, and the event drew lot of its inspiration from sufistic philosophy and we wanted the car’s name to relate to this message. After a bit of deliberation, the name ‘Rumi’ was proposed after the great 13th century poet, sufi mystic and scholar Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi. Rumi’s thoughts and practice revolves around humanity, love, compassion, tolerance, and respect for others. This aligned perfectly with the festivals message.

Moreover, his works have been translated to a number of languages and is widely recognised in the west. In short, Rumi’s name ticks all the boxes and therefore it was a no brainer to name the car after him.

Naming the car, gave a sense of direction to the design development process. Just as Rumi tried to create an atmosphere of dialogue and tolerance through his writing and poetry, I wanted the imagery to give a sense of discovery and conversation.

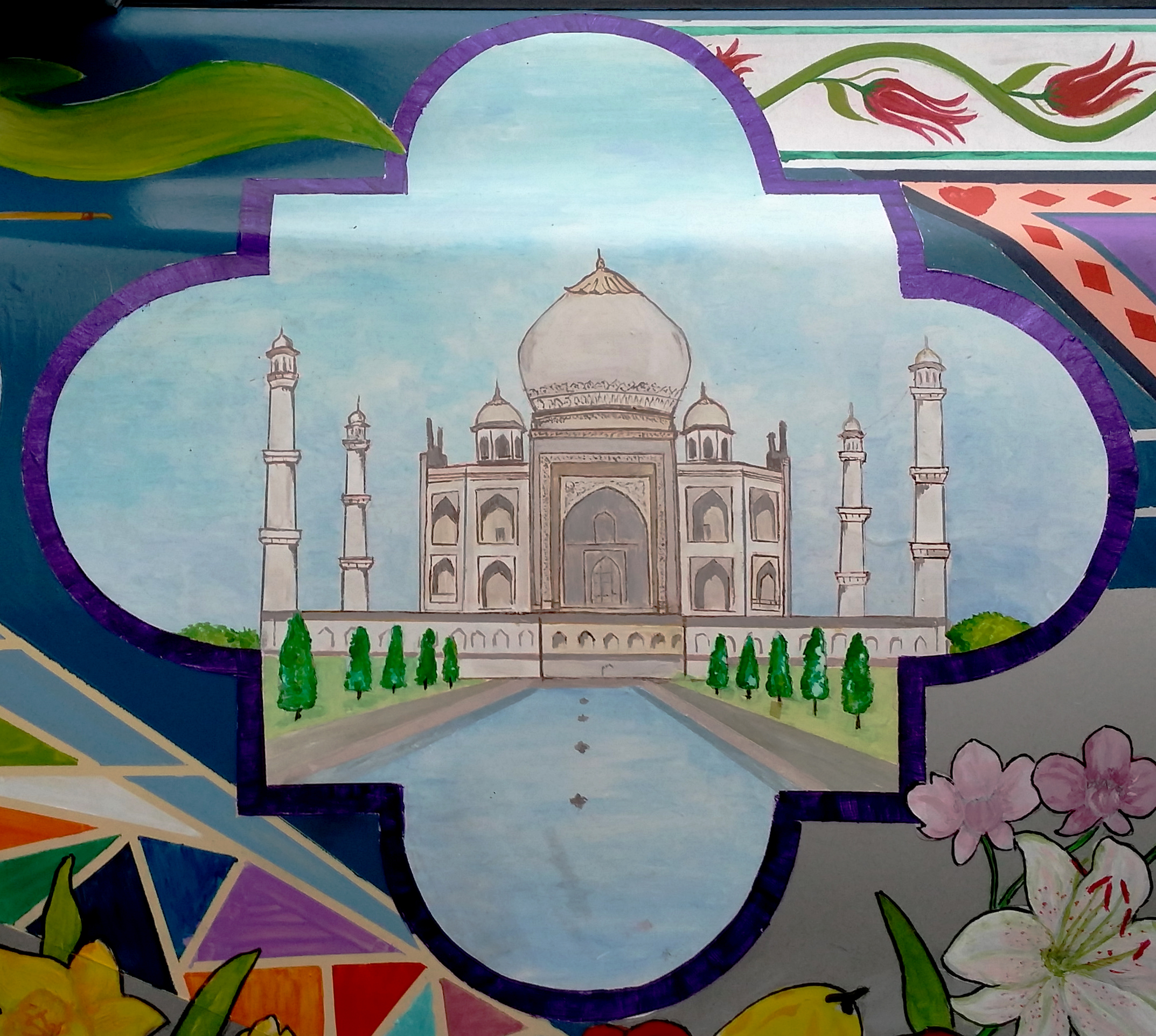

Given the cultural diversity that exists within people who identify as Muslim, I felt it was important to make clear and highlight that; like other ethnic groups, 'Muslims' are not one homogeneous group of people, but are impacted by their unique history and cultural heritage. I sincerely believe recognition of this fact, is important to avoid 'branding' and promote assimilation and harmony within our society.

They are 1.6 billion Muslims in the world. The challenge was to capture the diverse nature of the people and cultures within this group in a format that acknowledges their heritage and yet maintains the affiliation with the faith. I started collecting motifs and designs from various Muslim countries which were unique with the region and soon enough, I had an album of images of Muslim countries floral emblems, textile patterns, traditional arabesque and geometric designs to work with. With so many countries to look into, it was not practical to include motifs and symbol from each and every Muslim country in the world; I therefore decided to group the nations into identifiable regions.